OKLAHOMA CITY (KFOR) – “She was super resilient, very kind,” Haylee Blankenship said. “She wore her heart on her sleeve.”

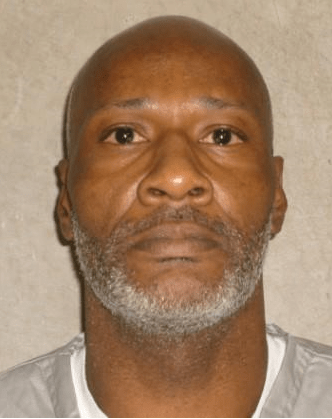

Haylee’s mother, Andrea Blankenship, was 41 years old when a stranger who was just weeks out of prison forced his way into her Chickasha home, killed her and carved out her heart. Police say Lawrence Anderson then went down the street to his uncle’s house, attacked his own family members and brutalized them with such force that his elderly aunt was left blind in one eye. His uncle and four-year-old cousin did not survive.

“God didn’t do this,” Delsie Pye said. “The devil did it, and we got to get it straightened out, because that shouldn’t have happened. He shouldn’t have been out.”

Delsie Pye still cannot believe her nephew was even out of prison; he had been serving a 20-year sentence but was suddenly set free earlier this year.

“You still think it was wrong he was let out?”

“Yeah. Yeah. Twenty-year sentence. Three years.”

Only three years served on a 20-year sentence.

“The system is what did it,” she said. “He shouldn’t have been out.”

Anderson had been in prison twice before. The first time was for pointing a gun at his girlfriend, and the second time was for selling crack cocaine near an elementary school. He applied for commutation in July 2019. It was denied, but Anderson was back on the docket three months later, and by January 2020 the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended commutation to Gov. Kevin Stitt, and Stitt approved it.

“They’re supposed to first look at the criminal history of the offender,” Payne County District Attorney Laura Thomas said.

Thomas never prosecuted Anderson, but she is often up against the same pardon and parole board that recommended his release.

“They’re not listening to victims, and they don’t want to hear them,” Thomas said. “They’re not listening to prosecutors, and they call us barbarians.”

“He shouldn’t have been able to go up for commutation, because of his criminal record,” Haylee Blankenship said. “They let him out, released him early, and three weeks later he murdered his own family and my mom.”

In 1998, Gay Carter was stabbed to death by inmate John Grant. Carter was a cafeteria worker at the Dick Conner Correctional Facility near Hominy.

“I was working the day she was killed,” Pam Carter, Gay Carter’s daughter, said.

Grant had been serving time for three robberies with firearms. One of his last crimes would be stabbing the 58-year-old mother to death with a shank.

“I was there, and I saw mom on the ground, but I got to say, ‘Mom, I love you.’ I got to say, I got to holler, ‘Mom, I love you,’ before I had to get out of the way,” Pam Carter said.

Grant was executed last month, but before that he had sought clemency from the Pardon and Parole Board. Despite his history of violence while in prison, two board members voted in favor of his clemency, Kelly Doyle and Adam Luck.

“I went online, and I applied for the parole board, and it was kind of a joke. I was like, ‘Why would they ever pick someone like me who is such an advocate for people coming home and decreasing the number of people we have in prison, because we are over incarcerating in this state,” Doyle said in 2019.

There has been controversy about Doyle’s position on the board coupled with her employment helping newly released inmates find jobs. In question is a conflict of interest.

In 2019, she was asked if her organization receives state funding.

“We have a federal pass-through grant through the Department of Human Services,” Doyle said. “And then we also have a contract that we were awarded prior to me getting on the Board.”

Court documents allege that organization has since received more than one million dollars in funding.

“That’s a privately run program,” Grady County District Attorney Jason Hicks said. “I would be a whole lot more comfortable with the Department of Corrections programs inside the prisons, and before somebody is eligible for parole, before they are released, they have successfully completed the programs that have been deemed necessary for that offender.”

“Run by the state and not privately.”

“Yes.”

“And why is that?”

“I think there is a fairly big incentive for somebody who is in private industry to just kind of move them along, I guess, to pad their statistics, and I’m not accusing anybody of anything, but the incentive is there so that they continue to get the paycheck and more and more people coming in.”

That alleged conflict of interest was shot down when the Oklahoma Supreme Court rejected a request to remove Doyle from the board.

“You get to this Pardon and Parole board who is making blatant partisan comments and taking positions that are not within the stated mission of the Pardon and Parole Board but a politically active position,” Thomas said.

In emails between Doyle and other board members, Doyle states she does not believe victims of violent crimes or prosecutors should be heard at Pardon and Parole Board hearings.

“We cannot protect the public when this is allowed to occur, and the public does not understand what is happening,” Thomas said.

Even Doyle herself admits there are problems with the commutation process.

“Now everybody is applying for commutation,” Doyle said. “So, the problem is, is that the commutation process, one, is not designed for this type of numbers. Two, what I get in a first-stage commutation is a handwritten account by the person who’s incarcerated. I have no verification if what they’re telling me is accurate. I have no verification of whether their crime and sentence are what they are. They just scan them, upload them, send it to me, and I have to vote yes or no in the first stage of whether we think that this deserves a second look. And in the second stage we’ll get the investigator’s report.”

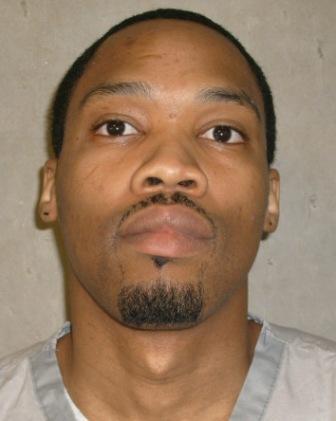

But that is not always accurate either. During the second stage of former death row inmate Julius Jones’ case, an investigator missed three misconducts including a positive drug test, lying about his violent past and using another inmate’s PIN number to make phone calls. According to longtime defense attorney, Irven Box, the fact that Jones still received a commutation hearing sets a new precedent.

“If I have a parole meeting coming up six to eight months from now, and they say, ‘Hey, Irven, we can’t hear this guy. He’s had a misconduct back whenever. I’ll say, “What about Julius Jones? He’s had three misconducts and he got a hearing,” Box said.

“I don’t think there is any question that it’s opened up a can of worms,” Hicks said. “It’s going to put more work on the parole board. It’s going to put more work on the investigators with the Department of Corrections. It’s going to put more work on the district attorneys, and it’s going to put more stress onto the families of the loved ones who have been murdered.”

“My whole life has changed. I’m completely different,” Haylee Blankenship said. “I do trauma therapy.”

“It’s been real hard,” Delsie Pye said. “I can’t sleep at night.”

“Their mission is to reduce Oklahoma’s prison populations,” Thomas said. “They don’t really care how they get there.”

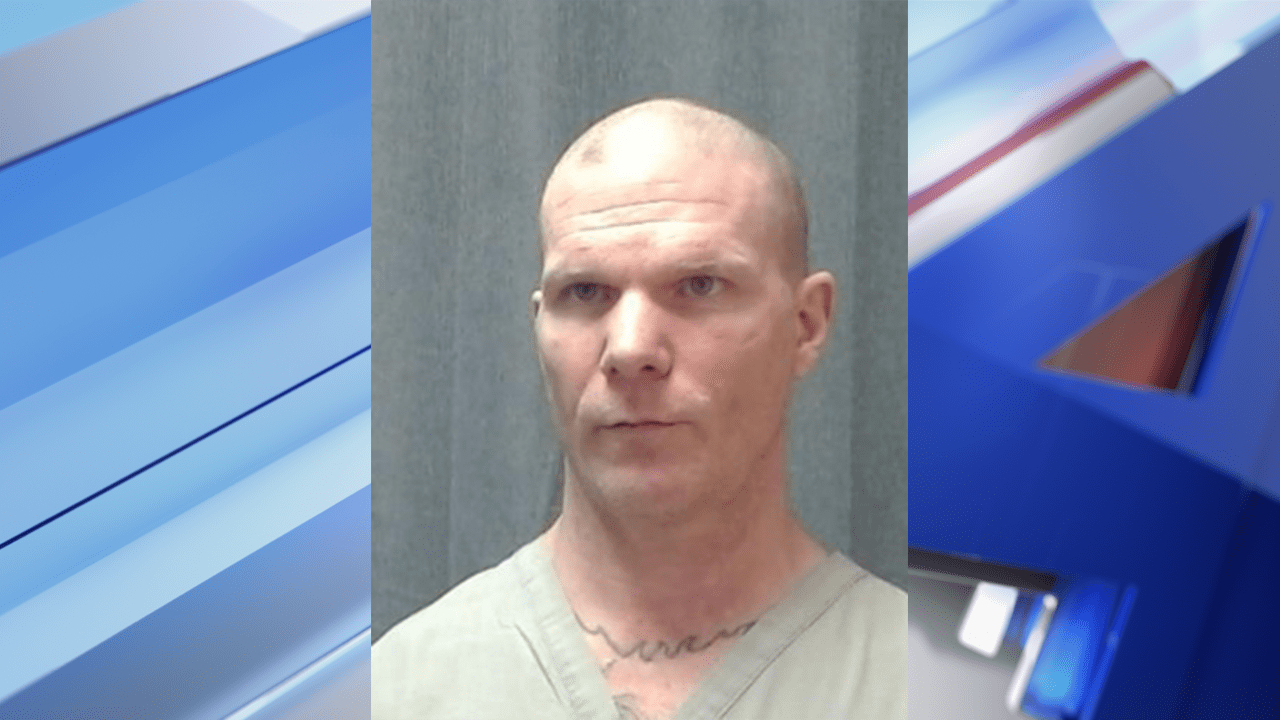

Last week the Pardon and Parole Board also recommended clemency for Bigler Stouffer who is set to be executed on Dec. 9. A federal judge denied the request. Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor responded to that decision and stated the board’s decision was “improperly based on whether an inmate will suffer pain during an execution. This concern is not a concern for the Pardon and Parole Board…instead, it is a concern of the courts. The courts…have spoken.”

KFOR’s request to the Pardon and Parole Board for an on-camera interview went unanswered.